Math in the News: Monty Hall Strikes Again

I apologize in advance for the fact that this references an article that is four months old. However, given the connection between the Monty Hall problem and popular culture, it cannot rightly be overlooked here, and this article from the New York Times allows us to discuss this problem from a unique perspective.

The Monty Hall problem is so named because of its origins in the game show "Let's Make a Deal." The problem itself is famous for having a completely counterintuitive solution, and my goal after discussing the problem and its relationship to the New York Times article on cognitive dissonance will be to explain where this disconnect between the problem and our intuition arises.

Here is a rigorous and unambiguous statement of the problem:

Suppose you're on a game show and you're given the choice of three doors. Behind one door is a car; behind the others, goats. The car and the goats were placed randomly behind the doors before the show. The rules of the game show are as follows: After you have chosen a door, the door remains closed for the time being. The game show host, Monty Hall, who knows what is behind the doors, now has to open one of the two remaining doors, and the door he opens must have a goat behind it. If both remaining doors have goats behind them, he chooses one randomly. After Monty Hall opens a door with a goat, he will ask you to decide whether you want to stay with your first choice or to switch to the last remaining door. Imagine that you chose Door 1 and the host opens Door 3, which has a goat. He then asks you "Do you want to switch to Door Number 2?" Is it to your advantage to change your choice?1

Of course, those of you familiar with the problem already know its solution: you are twice as likely to win a car if you switch doors.

There are many arguments for why this is true, but for the sake of brevity let's only look at one. Assume that you pick door number 1 (the odds will be the same if you pick door 2 or 3). If the car is behind door 1, then clearly you will lose by switching. However, if the car is behind door 2, Monty Hall is forced to show you what is behind door 3, and so by switching you will win. By an analogous argument you will win if the car is behind door 3. Thus, if you switch, you will win if the prize is behind door 2 or door 3, and lose if the prize is behind door 1. Since there is a 1/3 chance the prize is behind door 1, and a 2/3 chance the door is behind door 2 or 3, we see that it is always in your best interest to switch.

The New York Times article linked above shows this counterintuitive problem is important to understand not just if you are a fan of probability - the problem can arise in seemingly unrelated fields. In particular, it seems to be at the heart of a logical fallacy in a classic psychological experiment.

Here is a description of the experiment, involving M&Ms and monkeys, as taken from the article linked above:

For half a century, experimenters have been using what’s called the free-choice paradigm to test our tendency to rationalize decisions. This tendency has been reported hundreds of times and detected even in animals...

The Yale psychologists first measured monkeys’ preferences by observing how quickly each monkey sought out different colors of M&Ms. After identifying three colors preferred about equally by a monkey — say, red, blue and green — the researchers gave the monkey a choice between two of them.

If the monkey chose, say, red over blue, it was next given a choice between blue and green. Nearly two-thirds of the time it rejected blue in favor of green, which seemed to jibe with the theory of choice rationalization: Once we reject something, we tell ourselves we never liked it anyway (and thereby spare ourselves the painfully dissonant thought that we made the wrong choice).

But Dr. Chen says that the monkey’s distaste for blue can be completely explained with statistics alone.

How does this relate to the Monty Hall problem? The monkey's stated preference of red over blue is analogous to Monty's choice of which door to open. Once the monkey shows that he prefers red to blue, there is a 2/3 chance he prefers green to blue as well.

To see why this is true, let's list out all possible orderings of the monkey's M&M preferences. We already know that red is preferred to blue, so this eliminates some potential orderings (it brings the total number down from 6 to 3). The remaining choices are:

Red > Green > Blue

Green > Red > Blue

If we are constrained by the preference of red over blue, then we see that of the three potential orderings of preferences, green is also preferred over blue two times out of three. So is choice rationalization going on, or is this merely an exercise in probability? Certainly it suggests that no conclusions can be drawn by a 66% chance of green trumping blue - this is what one would expect. One would hope that this is an isolated case, and the majority of cognitive dissonance theory is immune from Monty Hall's crafty ways, but if the article is any indication, there isn't entirely a consensus on whether or not this is the case.

Sometimes in mathematics, one encounters a problem whose solution is so counterintuitive that even when one completely understands the path to the solution, and is certain this path is correct, the final answer seems too strange to be true. One can simultaneously know the answer to be right, and still not believe it. For many people, the Monty Hall problem seems to fall into this category. Why does it conflict so much with our intuition, and how can we make peace with this seeming contradiction?

The answer to the first question is clear: we intuitively expect the probability of success if we switch to be 50%. There are two doors, one has a prize and one doesn't, so there should be a 50/50 shot, right? And indeed, such a claim is supported by the statement that given doors 1, 2, and 3, the probability that the prize is behind door 1 given that it is not behind door 3 is 50%.2 So, what goes wrong?

What goes wrong is that, in asserting there is a 50/50 shot, we are forgetting the rules of the game. Monty Hall doesn't show us one of the doors with a goat and then ask us to pick one of the remaining doors; we pick a door first, and based on our choice, Monty Hall picks a door to show us. Our odds increase to 66% because Monty can never reveal what's behind the door we've chosen. This is important: this tells us that if we pick a door with a goat, Monty is forced to show us the other door with a goat - he has no choice in which door he can reveal.

Let's imagine a variation on the problem: one in which Monty still reveals a goat, but he can reveal what's behind the door we chose (provided we have not chosen the winning door). In the event that he shows us what's behind our door, we are allowed to choose again between the two remaining doors. Assuming the hosts selects the doors at random, the odds are now in line with our expectations: there is a 50/50 chance of winning the car.

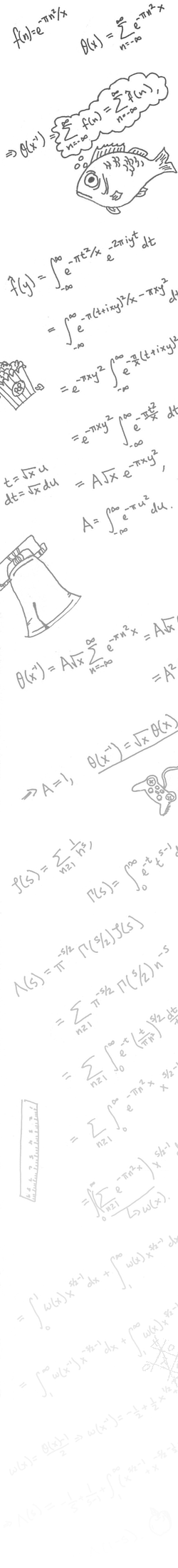

The reason why can be found in the following diagram. Here we assume that you will always switch, given the choice between staying or switching, and when you do have to choose again, you choose randomly. Also, as before, we assume that initially you choose door number 1 (the probabilities are the same if you initially choose door 2 or door 3).

You can click on the above image for a larger view.

You can click on the above image for a larger view.Since 1/6 + 1/6 + 1/12 + 1/12 = 1/2, indeed we see that in this modified game, you gain no advantage from switching.

What do we conclude? The advantage in switching in the classical Monty Hall problem comes from the fact that our choice of door can potentially restrict which door Monty shows us. In this modified version of the game, Monty has no restriction other than the fact that he can't show us the car. When the host is allowed to show you either one of the bogus doors, regardless of which door you pick, then the advantage to switching vanishes. Once this subtlety is understood, hopefully the seeming contradiction becomes untangled.

For discussion of some other versions of the Monty Hall problem, a good place to start is this Wikipedia article. And for those of you who are still unconvinced, this interactive simulation of the Monty Hall problem will, I hope, bring you to the light.

Make sure to join us next time!

1. Krauss, Stefen and Wang, X.T. (2003). "The Psychology of the Monty Hall Problem: Discovering Psychological Mechanisms for Solving a Tenacious Brain Teaser," Journal of Experimental Psychology: General 132(1). Retrieved from http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/MontyHallproblem.

2. Let A, B, and C be the events that the car is behind door 1, 2, and 3, respectively. We want to show what our intuition tells us: given the car isn't behind door 3, the probability it's behind door 1 is 50%. For those with some background in probability, this is a straightforward exercise in conditional probability. Using the given notation, we have

P(A | not C) = P(A and not C)/P(not C).

But P(A and not C) = P(A), since if the car is behind door 1, clearly it is behind door 1 and not behind door 3, and vice versa. Thus

P(A | not C) = P(A)/P(not C) = (1/3)/(2/3) = 1/2, as desired.

Psst ... did you know I have a brand new website full of interactive stories? You can check it out here!

comments powered by Disqus