Optimal Base Running

Now that the World Series is upon is, I thought I might take a moment to discuss the latest results in the field of optimal base running. On the face of it, this may seem like a non-issue; after all, as any decent student of geometry will tell you, the shortest distance between any two plates is a straight line.

In a game of baseball, however, it's more important to minimize time, not distance. Given this, running a path that consists of four straight lines connecting each base is not optimal, because the runner must slow down to make the sharp turns at each base. Of course, baseball players already know this, which is why they often swing out in their path before crossing first when they are confident that they can reach second or more. But still, the question remains: are these trajectories optimal?

According to a trio of mathematicians from Williams College, maybe not. According to an article originally posted in May, but which only now seems to be gaining some traction, recent graduate Davide Carozza wondered what would happen if runners began to curve immediately when leaving the batter's box. His conclusion may be somewhat surprising: using a circular path around the bases rather than a straight line path resulted in a 25% faster loop around the pitcher's mound.

Brian Wilson likes those odds.

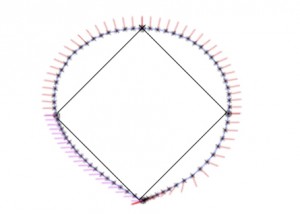

But of course, a circular loop doesn't seem like the most efficient route either - after all, once you return to home you don't need to run again, so it always makes sense to run as straight as possible from 3rd to home. Upon further analysis, Professor Stewart Johnson found that the fastest loop indeed one that begins like a circle, but comes in closer to the bases on the last leg of the journey.

Here is the proposed optimal path.

As with any mathematical model, some caveats are in order. The most significant one concerns acceleration - the red lines in the image above denote the acceleration, and you can see that all the lengths are the same, meaning that acceleration is assumed to be constant. But of course, this isn't really true when a batter is running the bases - as the latter article points out, "a runner may not be able to speed up as quickly while running along a curved path as he can along a straight one. In that case, some form of a banana path might make sense, allowing a runner to go straight for the first few critical seconds." Also, when the runner knows he hasn't hit more than a single, it obviously makes little sense to run in a curved path. Instead, it should be obvious that the wisest move is for the runner to get to first as quickly as possible.

Even bearing these warnings in mind, though, there still might be a good idea here worth exploiting. If the ball is hit between two outfielders and the runner is fairly certain of a double (or better), how much of a curved trajectory should he take? These are questions that could be answered during practices, and in a game where a fraction of a second can be the difference between a safe and an out, the answers might certainly have some applicability.

I would especially like to consider the San Francisco Giants to take these ideas to heart. They need every run they can muster, and even though this team looks like a strong contender to bring San Francisco its first World Series title, a little mathematical advantage couldn't hurt. After all, striking beard fear into the heart of your enemies can only take you so far.

My betrothed, sporting a most fearsome beard.

Psst ... did you know I have a brand new website full of interactive stories? You can check it out here!

comments powered by Disqus