How Hard Are Computer Games?

Every week, on days just like today, millions of Americans are afflicted by the debilitating condition known as The Mondays. Urban Dictionary defines The Mondays as follows:

A day generally created for the purpose of making people wish they were someone else. The day you realize you have 4 days of work ahead of you and that they won't be going by fast at all. Symptoms generally include feeling like crap, wishing you were dead, or not showing up for work in general.

For sufferers, The Mondays can be quite painful. However, there are remedies that can alleviate some of these symptoms. For one, individuals can spend their day playing games on the internet, in an attempt to push their troubles into the darkest recesses of their minds. Minesweeper is a popular choice, as is Tetris, as any fan of Office Space knows (in fact, I credit this film with teaching me about the terrible condition known as The Mondays).

Or, if your case of The Mondays is so strong that you've already exhausted these options, you could try your hand at a newer game, such as Flood-It! In this game, released by LabPixies in 2006, the goal is to make a grid of squares all have the same color, but you start by only being able to change the color of the square in the upper left hand corner. By changing this square's color to match the squares adjacent to it, however, you can gradually increase the size of your mass in the upper left corner, and, like a spreading virus, try to capture every square in the grid. This explanation is admittedly sparse on details, but as you can see from the video below, the rules are quite simple.

While these are all suitable remedies for a severe case of The Mondays, it's natural to ask what these games could possible have to do with math. Well, as it turns out, each of these games is related to a problem of such importance, the Clay Mathematics Institute has named it one of the Millennium problems (recall that we briefly discussed the first Millennium problem to be solved). The problem in this instance is the famous P = NP? problem.

As with most things, Wikipedia has a treatment of this problem which you are welcome to read. However, it is a bit technical, so instead I offer you the Clay Mathematics Institute's introduction to the problem:

Suppose that you are organizing housing accommodations for a group of four hundred university students. Space is limited and only one hundred of the students will receive places in the dormitory. To complicate matters, the Dean has provided you with a list of pairs of incompatible students, and requested that no pair from this list appear in your final choice. This is an example of what computer scientists call an NP-problem, since it is easy to check if a given choice of one hundred students proposed by a coworker is satisfactory (i.e., no pair taken from your coworker's list also appears on the list from the Dean's office), however the task of generating such a list from scratch seems to be so hard as to be completely impractical. Indeed, the total number of ways of choosing one hundred students from the four hundred applicants is greater than the number of atoms in the known universe! Thus no future civilization could ever hope to build a supercomputer capable of solving the problem by brute force; that is, by checking every possible combination of 100 students. However, this apparent difficulty may only reflect the lack of ingenuity of your programmer. In fact, one of the outstanding problems in computer science is determining whether questions exist whose answer can be quickly checked, but which require an impossibly long time to solve by any direct procedure. Problems like the one listed above certainly seem to be of this kind, but so far no one has managed to prove that any of them really are so hard as they appear, i.e., that there really is no feasible way to generate an answer with the help of a computer. Stephen Cook and Leonid Levin formulated the P (i.e., easy to find) versus NP (i.e., easy to check) problem independently in 1971.

What do these games have to do with this problem? As it turns out, both Tetris and Minesweeper are NP-complete, while FloodIt! is at least NP-hard (you can learn about these definitions on Wikipedia if you're curious). Given the above description of the problem, however, it's natural to ask in what sense these three computer games are hard.

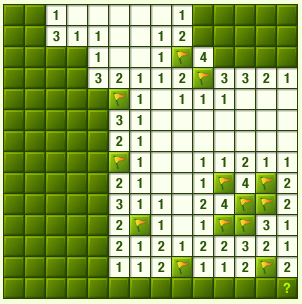

Minesweeper's NP-completeness was proven by Richard Kaye in 2000 (he discusses some of the ideas involved here). The game is NP-complete in the following sense: suppose you are playing a game of minesweeper, and you want to know whether a certain square has a mine behind it or not. One way you could do this is assume that there is a mine, and see if this leads to a contradiction by checking against the remaining possible configurations of mines. Generating all possible configurations, however, can be an arduous task if we just go case by case. In fact, using this method, most of the time a computer will not be able to solve the puzzle in any reasonable amount of time.

Is the lower right corner mined or not?

In other words, we want to check whether a given configuration of the board is consistent; that is, whether it could have come from a certain arrangement of mines. Given the underlying arrangement of mines for a game, it's easy to check whether the layout is consistent. But to find the solution to a given board using this idea quickly becomes very complicated.

Tetris, meanwhile, was shown to be NP-complete in 2002 (the paper is available on the arXiv). The Tetris game under study here, however, is a bit different from the one enjoyment by so many. Traditionally the game only ends when the player loses, and the player can only see one block ahead into the string of pieces that will eventually fall. In the version under study by Demain, Hohenberger, and Liben-Nowell, however, the game is played with a predetermined, finite number of blocks, and the player knows the full order in which the blocks will fall. They then discuss a number of NP-complete problems. Let me just highlight one: the problem of maximizing the number of rows cleared.

Given a sequence of plays in a Tetris game of this type, we can easily calculate the number of rows that were cleared. However, finding an algorithm that can optimize the number of cleared rows in a reasonable amount of time (i.e. polynomial time) remains at the heart of the P vs. NP problem.

The related question in FloodIt! is to find a solution to a given board in as few moves as possible. The fact that this problem is NP-hard was only recently proved, which I learned from this link on Slashdot.

So if you have a case of The Mondays, fear not: those games you play on your computer are certainly complex enough to give your brain a workout. And if you spend enough time on them, maybe you can discover algorithms to answer the questions raised here in polynomial time. Is it possible that with enough Tetris, you could play your way to a P=NP solution and a million dollars? Perhaps.

Psst ... did you know I have a brand new website full of interactive stories? You can check it out here!

comments powered by Disqus