Math on TV/Math Gets Around: Brooke Knows Best

Recently, I found myself thinking of mathematics in an unlikely set of circumstances: while watching VH1's latest "Celebreality" show, Brooke Knows Best. I realize that an admission like this may be embarrassing, and so it is for the sake of your edification, dear reader, that I am willing to go on the record with this deliciously shameful information.

For those of you who may not know, the titular character is the daughter of Santa with Muscles star and All-American hero, Hulk Hogan. In the show, Brooke lives in an expensive looking condo in Miami, goes to the beach, and sings her own theme song. This is about as much as I know. I swear.

The particular episode to which I would like to draw your attention (Episode 4) involved Brooke traveling to Panama City, Florida, to host some Spring Break parties. And I bet you thought math and spring break were incompatible.

Because of his overprotective nature (or because the producers thought it would make better television), Hulk Hogan decides that it's a good idea to tag along on these spring break adventures. He even brings his chubby, mullet-sporting friend in tow, and the two of them cause all kinds of PG-13 hilarity. It is as if they are the love children of the love children of Abbott & Costello and Schwarzenegger & Stallone.

One day, Hulk suggests that the group go visit The World's Largest Human Maze (or, as he calls it, "The World's Largest Human Maze in the world"). The maze in question is the Gran Maze of Panama City. Calling it the World's Largest Human Maze is a bit deceptive, as there are hedge mazes which are larger - however, to the maze's credit, it does not seem to refer to itself as the World's Largest Maze in any of its information.

In any event, they go to this maze: Hulk and his buddy as one team, along with Brooke and her two roommates as another. At some point during their travels through the maze, they decide to split up and make a competition out of it: whichever team can make it through the maze first will get to plan the agenda for the rest of the day. Hulk and his friend make it through first, but only by squirming underneath the wall panels. The other team, once they learn of this deception, declares Hulk's victory null and void.

There is certainly a moral here: don't cheat. But there is another important moral here, one I think may be lost on Hulk Hogan, even to this day. That moral is this: Hulk, you should have brushed up on your maze-solving algorithms!

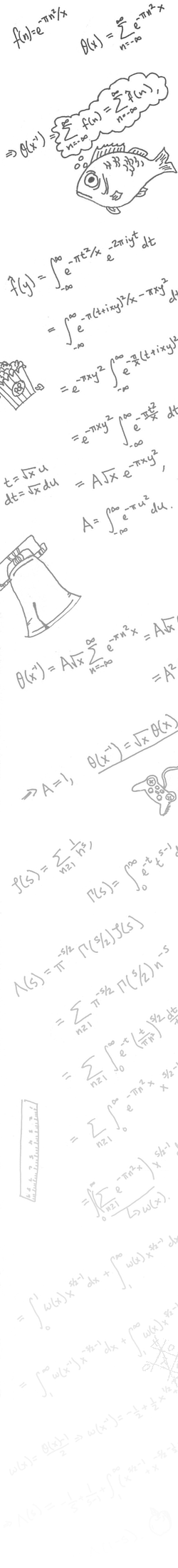

Indeed, there are a number of procedures one can follow in order to try and solve a maze. Perhaps the most well known is the Wall Follower algorithm. In this procedure, you walk through the maze keeping either your left or right hand in contact with the wall of the maze at all times. If you do this, without removing your hand from the wall, you will eventually find the exit. Here is an example:

Solving a Maze: The Wall Follower algorithm.

Solving a Maze: The Wall Follower algorithm.This maze was constructed using the Maze Maker.

Now, the astute reader may realize that unfortunately, this method will not always lead you to the end of the maze. Even in a simple example, such as the one below, it is easy to see that regardless of whether you follow your left hand or your right hand, you will merely circle the entrance and never reach the end.

So, how do we know if the Wall Follower algorithm will work? This algorithm will always lead us to the exit (provided there is one) as long as the maze itself is simply connected. Less rigorously, when the maze cannot be solved using this algorithm, it is because the maze is in separate pieces. In the example above, we see that the piece of the maze that surrounds the start is disjoint from the rest of the maze.

Why, then, does this algorithm work if the maze is simply connected? Because every simply connected maze can be continuously deformed to a circle (i.e. such mazes are homeomorphic to the circle). Once we deform the maze to a circle, it is obvious how the wall follower algorithm works: it is equivalent to simply tracing your way along a circle between two points. This video does a better job explaining what goes on:

So, had Hulk confirmed that this human maze was, in fact, simply connected, he could have used this algorithm to try and beat his daughter fair and square. However, what if the maze is not simply connected? Indeed, a zoomed in view of the maze, courtesy of Google Maps, is somewhat inconclusive. How then, could Hulk guarantee that he would eventually make his way out?

View Larger Map

For more general mazes, we can turn to another algorithm: Tremaux's algorithm. This algorithm will lead you to the exit even in mazes that are not simply connected. However, Tremaux's algorithm also requires something that the Wall Follower algorithm does not: namely, you must have some way of marking your path.

The algorithm can be described according to the following rules:

- Walk down the maze, drawing a line behind you.

- When you come to the first intersection, choose a path at random and follow it.

- When you come to a dead end, turn around and return to the last intersection.

- If you are walking down a corridor that you have not been down before, and you come to an intersection you have already visited, treat the intersection as a dead end and turn around.

- If you are walking down a corridor that you have been down before, and you come to an intersection (necessarily one you have already visited), then go down a path which you have not visited yet, if possible. If this is not possible, go down a path you have only been down once.

Rule 5 may look restrictive, but in fact, with this algorithm you will never need to walk down the same corridor more than twice. If the maze has a solution, this algorithm will find it. Moreover, once you have used this algorithm to find a solution, the corridors marked only once will trace out a direct path to the finish.

Solving a Maze: Tremaux's algorithm. Notice that no

Solving a Maze: Tremaux's algorithm. Notice that nocorridor is traveled more than twice, and the ones

traveled exactly once trace a direct path to the finish.

So there you go, Hulk. Two methods you could've used to try and defeat your daughter fair and square. Granted, there is no guarantee that following these procedures would have gotten you through any faster than your daughter, but they certainly wouldn't have disqualified you from victory. Instead of being able to savor your win, you were called a cheater, and your prize was revoked.

Let this episode serve as a lesson to aspiring professional wrestlers everywhere: math can be of service, even to you.

For more on maze algorithms (both algorithms for creating mazes, or for solving them), this website offers a treasure trove of useful information. Hopefully Hulk Hogan will do his research the next time he makes such a mathematical challenge.

Psst ... did you know I have a brand new website full of interactive stories? You can check it out here!

comments powered by Disqus