The Probability Games

Though we are still a few months away from the start of the summer blockbuster season, the scuttlebutt is that The Hunger Games, opening this weekend, is expected to do huge business (and by huge, I mean upwards of $100 million). Based on the 2008 Suzanne Collins book of the same name, this property is the hottest new thing in the realm of young adult fiction, and in this post-Harry Potter, nearly-post-Twilight era of cinema history, the timing could not be better for movie executives. The book is the first of a trilogy, so whether you like it or not, these films will be with us for the next few years.

If you have not read the book, or have no idea what I'm talking about in general, a trailer for the film can be found here (sorry, embedding has been disabled for the video). The story takes place sometime in the future, many years after a war that has seemingly decimated the population. The United States is now broken into twelve districts, all under control of an totalitarian regime headquartered in the aptly-named Capitol. Every year the Capitol organizes the Hunger Games, in which one young man and one young woman between the ages of 12 and 18 is selected from each of the twelve districts to compete in a fight to the death (if this sounds a lot like a certain Japanese book/film combo to you, you're not the only one). The story begins when 16 year old Katniss Evergreen volunteers to fight in the Hunger Games in place of her younger sister Primrose, who is selected at the age of 12.

This selection process is where the story intersects with mathematics. Take a look at this passage from the first chapter of the book.

You become eligible for the reaping the day you turn twelve. That year, your name is entered once. At thirteen, twice. And so on and so on until you reach the age of eighteen, the final year of eligibility, when your name goes into the pool seven times. That's true for every citizen in all twelve districts in the entire country of Panem.The rules here practically beg for some mathematical analysis. Here are a few questions. What are the odds of being selected? How does the probability of a young adult being chosen over their lifetime increase with the number of tesserae she elects to receive?But here's the catch. Say you are poor and starving as we were. You can opt to add your name more times in exchange for tesserae. Each tessera is worth a meager year's supply of grain and oil for one person. You may do this for each of your family members as well. So, at the age of twelve, I had my name entered four times. Once, because I had to, and three times for tesserae for grain and oil for myself, Prim, and my mother. In fact, every year I have needed to do this. And the entries are cumulative. So now, at the age of sixteen, my name will be in the reaping 20 times.

To estimate values here, we need to know how many names are in the reaping. This is not such a trivial thing to estimate, since each child may have his or her name entered several times. To simplify our analysis, we will assume that (a) the number of names entered is the same for boys as it is for girls, and (b) this number is essentially the same from year to year. Our second assumption may not be terribly realistic, but since we're analyzing a fictional game in a fictional dystopia, I hope you will suspend your disbelief with me for the moment.

We can estimate the number of female names entered by estimating the number of girls in District 12 between the ages of 12 and 18, and the average number of tessarae each girl requests. First let's focus on the number of girls between 12 and 18. To start, it's mentioned several times in the book that the population of District 12 is around 8,000 (see here for a fun estimate of the population of the entire country). According to this census data, a bit less than 20% of the US population was between the ages of 5 and 17 in both 2000 and 2010. But it's a hard knock life in District 12, and the life expectancy is undoubtedly much lower than it is in present-day America. So let's assume that the percentage of 5 to 18 year olds is closer to 35% (this article suggests such a figure is not unreasonable). That puts the number of 5 to 18 year olds in District 12 at 2,800. Cut that number in half to focus on 12 to 18 year olds, and cut it in half again to get rid of the boys, and we have approximately 700 girls in District 12 who are eligible to participate in the Hunger Games.

Assuming a roughly equal number of girls of each age (i.e. 100 12 year olds, 100 13 year olds, and so on), this would mean that each girl has her name entered an average of 4 times, ignoring tesserae (since (1 + 2 + 3 + 4 + 5 + 6 + 7)/7 = 4). But how many tesserae will each girl request on average? Though the number of upper-class citizens whose children don't need to request tesserae is relatively small, it's not the case that every poor child will request tesserae, since it makes the most sense for the oldest eligible child to shoulder the entire tesserae burden. Therefore, even in poor households, we should expect no more than one eligible child to request tesserae.

Throughout, we will consider three cases: where the average number of tesserae requested is 1, 1.5, and 2. With our assumptions and a bit of work, one can show that if the average number of requested tesserae is t, the average number of times each girl's name is entered is 4(1+t). Therefore, the average number of times each girl's name is entered in each case is 8, 10, and 12. Since the number of girls is 700, this means that the estimated number of names in each case is 5,600, 7,000, and 8,400. Call the number n, whatever it may be.

Now let's suppose you are a girl and you plan on requesting t tesserae for your family every year you are eligible for the games. How does the probability of you getting picked increase with t? Well, when you are 12, the probability of being selected is nt+1, since there are n names entered, and t + 1 of them are yours. The probability of being in the games when you are 13 is equal to the probability of being selected when you are thirteen times the probability you were NOT selected when you were twelve (since, if you were selected when you were twelve, either you are dead or you were the winner of the previous Hunger Games - in either case, you won't be playing again). Therefore, the probability is

(1−nt+1)(n2t+2)

Similarly, you can only be selected when you are 14 if you WEREN'T selected when you were 12 or 13, so the probability of being selected at 14 is

(1−nt+1)(1−n2t+2)(n3t+3).

By now you should see a pattern emerging. Perform this calculation for every age from 12 to 18, add them all up, and in fancy math notation we find that the probability of being chosen is equal to

nt+1k=1∑7kj=0∏k−1(1−j(nt+1)).

We can now use our above estimates for n to see how this number varies with t. For example, with n = 5600 and t = 0 (i.e. if we assume you never request tesserae), the probability you will be selected is 1/5600 + (5599/5600) × (2/5600) + (5599/5600) × (5598/5600) × (3/5600) + ... . Adding up all these numbers gives a probability of roughly 0.499%.

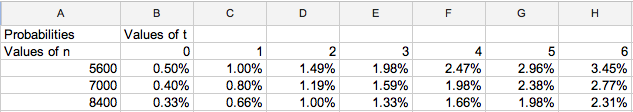

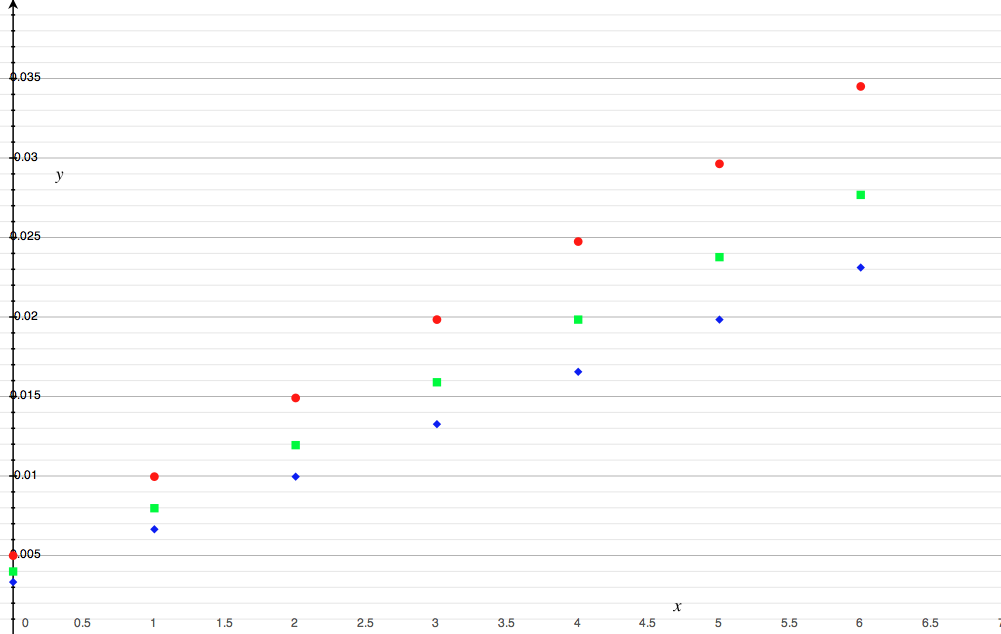

Other combinations can be found in the following chart:

The x-axis represents number of tesserae requested. Red corresponds to n = 5600, green to n = 7000, blue to n = 8400.

The chart above tells us, for example, that if we use the estimate of n = 5600, then a girl requesting 3 tesserae every year has a roughly 2% probability of being selected for the Hunger Games over the 7 year span when she's eligible. If n = 8400, that probability drops to around 1.3%.

In each case, we see the number of tesserae acts as a sort of multiplying factor. If you request one tesserae, you roughly double your chances of being selected. If you request two, you roughly triple your chances, and so on. It's not hard to see why this should be the case, from what we've already done. For example, if n = 5600 and t = 0, the probability of being selected when you're 13 is equal to 5599/5600 × 2/5600, but this is nearly the same as just 2/5600, since 5599/5600 is nearly 1. Similarly, the probability of being selected when you're 13 is 5599/5600 × 5598/5600 × 3/5600), but this is again roughly equal to just 3/5600. By replacing all the probabilities of not being selected by 1, we see that the probability of being selected is approximately equal to just

nt+1+2nt+1+3nt+1+…+7nt+1,

or simply

n28(t+1).

This formulation is much simpler, and shows clearly how the probability increases with t. Note that this estimation only works when n is much larger than t; but since that always seems to be the case when it comes to the Hunger Games, we should be ok.

So, while Katniss increased the probability that she would be selected by a factor of 4 by planning to request 3 tesserae every year, in absolute terms, the probability that she would be selected is still relatively small. Even so, the probability that her younger sister would be selected in her first year is even smaller, and yet the whole series begins with the occurrence of this unlikely event. The moral here is clear: while you can try to hedge your bets, there is no surefire way to prevent a loved one from playing the Hunger Games. Unless, of course, you are willing to trade your fate for the one you love.

(If you're interested in the raw data from the chart, you can find it below.)

Psst ... did you know I have a brand new website full of interactive stories? You can check it out here!