Playoff Probabilities

Continuing with last week's theme, and since we are in the midst of playoffs, I'd like to take a moment now to discuss another link between baseball and mathematics. This link is particularly timely since the scuttlebutt on the internet suggests that next year the playoff rules for baseball will be changed: the number of teams competing for the World Series will increase from 8 to 10, and because of that, another round of playoff games will be introduced.

Currently, the playoffs consist of three rounds. The first round is the Division Series, in which eight teams compete in a best-of-five match-up (equivalently, a first-to-three match-up, i.e. the first team to win three games wins the series). The second and third rounds, better known as the Championship Series and World Series, are composed of four and two teams, respectively, but are both best-of-seven (equivalently, first-to-four). Because of these three rounds of several games each, the playoff season is already quite long; therefore, the new proposed playoff round, it has been suggested, would be composed of either a single game between competing teams, or a best-of-three (first-to-two) series between the two teams.

Many people take issue with such a short series on the grounds of fairness. In a season where each team plays 162 games, they say, it's not fair for a team's World Series hopes to ride on a single game, or even a short series composed of at most three games. There are even those who suggest that the Division Series is too short, and that all three of the current rounds should be a best-of-seven. These are noble sentiments, but are they reasonable? We can use mathematics to try and answer this question.

Suppose two teams are meeting for a playoff series, and the probability that one team (call it, I don't know, the Giants) will win a single game is p (this model is fairly simple, and does not take into account advantages associated with the starting pitcher, for example, but let's keep things basic for now). Then the probability that this team will win a one game series is again p, since the series consists of a single game.

What if the series is three games long? In this case, the Giants will win if they win the first two games, or split the first two games and win the third game. So there are three outcomes: WW, WLW, or LWW. The probability of the first event is p2, while the probability of the second and third events are both p2(1 – p) (probability p of success is the same as probability 1 – p of failure). Adding these three probabilities gives the total probability that the team will win a best-of-three series:

p2 + 2p2(1 – p) = p2(3 – 2p).

In a best-of-five series, the Giants will win if they win three in a row, two of the first three and the fourth, or two of the first four and the fifth. Using combinations to count the possibilities, we see that in this case, the probability of the Giants winning the series is equal to

p3+(23)p3(1−p)+(24)p3(1−p)2

p3(10 – 15p + 6p2).

With the same type of argument you can calculate the probability that the Giants win a best-of-seven series. I'll spare you the details: the result is $latex p4(35 – 84p + 70p2 – 20p3).

In each case, the probability of winning the series is a polynomial in p, the probability of winning a single game. But how to these polynomials compare? Let's turn to technology to lead the way!

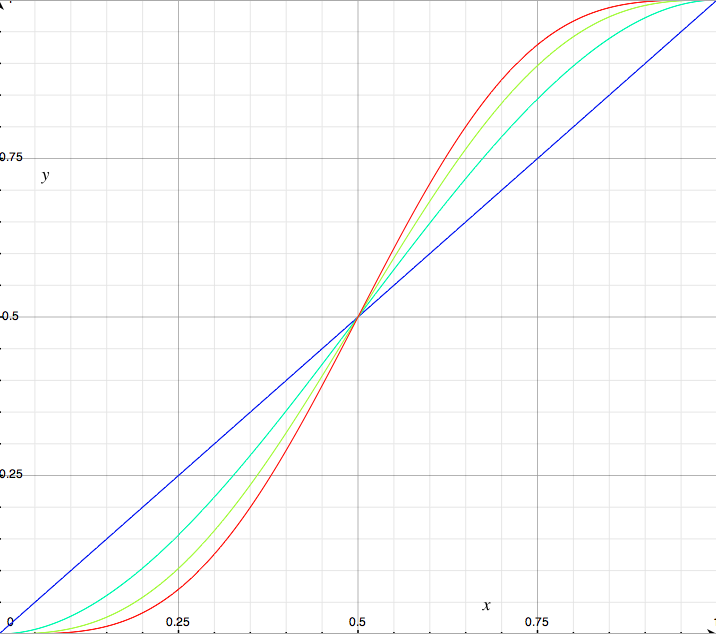

Probabilities for a one, three, five, and seven game series.

Above is a graph of these four functions - the x-axis represents the probability p, while the y-axis represents the probability of winning the series. The dark blue graph is for a single-game series (the function is p), the light blue graph is for a three-game series, the light green graph is for a five-game series, and the red graph is for a seven-game series. What can we deduce from the picture above?

First, note that a longer series benefits the stronger team more than the weaker team - this makes intuitive sense, if you think about it. Also, for teams that are perfectly evenly matched (i.e. p = 0.5), the length of the series doesn't affect the probability of winning the series, which is also 50% in each case.

But what about teams with a slight, moderate, or strong advantage over their competition? How does the length of the series affect the probability of winning the series? Let's look at a small table of values, in the cases p = .55, p = .6, and p = .7.

| p | Best of One Probability of Success | Best of Three Probability of Success | Best of Five Probability of Success | Best of Seven Probability of Success |

| .550 | .550 | .575 | .593 | .608 |

| .600 | .600 | .648 | .683 | .710 |

| .700 | .700 | .784 | .837 | .874 |

As you can see from the table (or the graph), the more evenly matched the teams, the less of a difference the length of the series makes. If your team has a 55% chance of winning a given game, the advantage in a seven game series is increased by a little less than 6 percentage points. With a 60% chance of winning a given game, the advantage in a seven game series is increased by 11 percentage points, and with a 70% chance of winning a given game, the advantage in a seven game series is increased by over 17 percentage points.

Not also that the change from a best-of-five series to a best-of-seven series isn't really very large. Even if your team is heavily favored (70% probability of winning each game), the change from a best-of-five series to a best-of-seven series is less than four points. With more evenly matched teams, the difference is even smaller, suggesting that expansion of the Division Series from a maximum of five to a maximum of seven games isn't necessarily a great idea.

On the other hand, the largest change in probabilities is between the jump from a best-of-one series to a best-of-three series. While the change isn't so significant for evenly matched teams (and more evenly matched teams would be most likely to play each other in this round under the suggested rule changes), for match-ups in which one team is heavily favored, the difference can be more significant.

Whether or not one wants longer series or shorter series depends, I suppose, on one's baseball philosophy. It certainly seems like having everything ride on a single game after a season of more than 150 games is a little unbalanced, but from a mathematical standpoint, the stronger team will most likely gain only a small advantage by moving to a three game series. Of course, this simplified model can only tell us so much, and it's possible that the advantages of a longer series are being underrepresented here. To err on the side of caution, I'd be more inclined to support a best-of-three series, though whether or not this is possible without stretching the season too long is something that the folks who are paid better than me to think about these matters will have to decide.

Psst ... did you know I have a brand new website full of interactive stories? You can check it out here!

comments powered by Disqus