Scoreboard Stats

A couple of weeks ago I noticed this article on the Yahoo Sports page, which highlighted a statistically rare event that occurred in the American League on Sunday, May 8th. On that day, 7 baseball games were played on the AL schedule, and in all of those games one team scored exactly 5 runs. The post then links to this article from the AP, which gives this rare event the following context:

It was the first time in 18 years that such a quirky thing happened with a full schedule. On Aug. 10, 1993, all seven NL games featured one team scoring precisely two runs, STATS LLC said.

The last time it occurred with five or more runs was July 20, 1955, when all four AL games had at least one team score exactly six, STATS LLC said.

When I read this article, some questions immediately came to mind: exactly how rare is it for one team in a collection of 7 baseball games to have a common score of 5? Also, if 7 teams in 7 games have the same score, which score are they most likely to share? Are the 7 games with a common score 0f 2 more or less likely to occur than the 7 games with a common score of 5?

We can answer these questions with some (relatively) simple probability models, given some caveats. I'd like to estimate these probabilities using only one parameter: the average number of runs a team scores during a game. Of course, that average will vary from team to team, and also from year to year (in particular, runs per game have declined from the heyday of steroid-mania that gripped baseball at the turn of the millennium). Due to different rules, there may also be variation between the American and National Leagues. Let me ignore this, though, and consider only an average number of runs per game overall - what we lose in precision we will more than make up for in clarity.

Ahh, the late 90's, when it was easier to sock a few dingers.

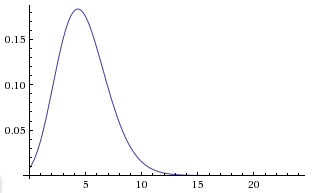

The question remains: how many runs are scored on average in a baseball game? I found some data online which is somewhat outdated, but I'll stick to it for convenience (and, more importantly, out of laziness) - any alteration in this number is easy to propagate throughout the following discussion. In this article from 2005, the author tabulated the average number of runs per game in MLB over a 5 year span from 2000-2004 (that's over 12,000 games!). He has a nice looking graph of the distribution of scores as well:

A savvy probability student might see the long tail of this probability distribution and liken it to the Poisson distribution, a distribution encountered in many probability courses, and which is frequently motivated by a desire to model "rare events." I put the term in quotations since what constitutes "rare" is frequently left undefined, and in any event, is not really pertinent to this discussion.

Let us suppose, then, that the number of runs scored per game by each team follows a Poisson distribution. French aside, this means that the probability a team will score n runs is equal to

e−An!An,

where A is the average number of runs scored per game — in this case, 4.82, and e is the unsung hero sometimes known as Euler's number. Don't worry too much about this formula; if you prefer, the graph of the function e−4.82n!4.82n looks like this (courtesy of Wolfram Alpha):

Note that the fit isn't perfect — this graph starts much lower at 0 than the graph of the actual data pictured above, for example — but there is precedence for using the Poisson distrubtion to model runs in a baseball game (this article provides one such example, but a subscription is required to view it in its entirety). More careful analysis is possible, and can be found in resources like this one, but again, I want to keep things relatively simple.

So, let us suppose that the probability that a team scores n runs is e−4.82n!4.82n. What then, is the probability than in a baseball game, one of the teams will score n runs? Either team A can score n runs or team B can score n runs, but they can't both score n runs since baseball games can't end in a tie. This means that the probability of A or B scoring n runs is simply the probability that A scores n runs plus the probability that B scores n runs, or 2e−4.82n!4.82n

For the odds that this happens 7 times, we then multiply this number by itself 7 times (lurking under this is the assumption that runs scored in different games are independent, which seems like an entirely reasonable assumption to make). To summarize, we estimate the probability that one team in each of 7 games scores n runs is

(2e−4.82n!4.82n)7.

If n = 5 (as it did earlier this month), the probability is roughly .064%. In other words, if 7 AL games were played every day, you would expect this outcome once every 1,560 days or so. Having said that, with more careful analysis it's possible to show that in fact, if 7 games will have teams scoring the same number of runs, 5 is the most likely number. For comparison, when n = 2 the probability is only a paltry 0.00812%, making what happened on May 8th over 75 times more likely than what happened on August 10, 1993. Of course, it's not fair to compare these records to the 6 run record in 1955, since in that case only 4 games were played, rather than 7. Nevertheless, it's not difficult to adjust this model from 7 games to 4 games (or an arbitrary number of games).

So, rather than some murky intuition telling us this event should be unlikely, with a little more effort we can attempt to quantify exactly how unlikely this event should be. More sophisticated models for runs could be used, but perhaps that is a topic I will save for another day.

Psst ... did you know I have a brand new website full of interactive stories? You can check it out here!

comments powered by Disqus